Integrating FQDN with AWX and GitLab

In this video, I explain how to implement FQDN in AWX and GitLab.

Below you will find a tutorial divided into two important parts. The first concerns Fully Qualified Domain Names, or FQDNs, and the second will show how to modify the configuration of CoreDNS in Kubernetes to forward traffic to an external DNS server’s IP address.

What is FQDN?

It is a complete domain name that uniquely identifies a host on the Internet. It consists of the hostname and the domain, providing a unique address. Why is this important? In the world of computer networks, clarity and precision are key. FQDNs allow for clear communication, eliminating any misunderstandings related to addressing.

Using FQDNs is also best practice in configuring services and network devices because they provide a constant point of reference, regardless of changes in IP addresses. Now that you know what an FQDN is and why it’s so important, let’s move on to the second part of our meeting.

Additional knowledge:

The term “fqdn” stands for Fully Qualified Domain Name. It represents the complete domain name for a specific computer, or host, on the internet or within a local network. The FQDN consists of two main parts: the hostname and the domain name, including the top-level domain. For example, in “rancher.local,” “rancher” is the hostname, and “local” is the domain name.

When I use FQDNs in configurations, particularly in my Ansible playbooks and AWX (Ansible for the web), I realize several benefits:

Clarity and Specificity: FQDNs are unique. By employing an FQDN such as “rancher.local,” I can clearly identify the target system without any ambiguity, which is essential in complex networks with numerous nodes.

Scalability and Management: In larger environments, FQDNs help me manage and scale my infrastructure more effectively. They allow me to easily track what roles and services are assigned to which machines, especially when integrated into configuration management and deployment systems like Ansible and AWX.

DNS Resolution: FQDNs collaborate with DNS (Domain Name System) to turn human-readable names into IP addresses that computers use for communication. By using FQDNs, I can manage hosts via DNS, which tends to be easier than maintaining IP addresses, especially if they change due to DHCP or other network management policies.

Flexibility: Adopting FQDNs offers me more flexibility in how I organize and access my systems. I can move services between hosts or change IP addresses without having to update every single reference to that host in my configurations—only the DNS record needs an update.

In my Ansible playbook (“updates-rancher.yml”), I use fqdn as a variable to specify the host or group of hosts the playbook should run against. By setting the fqdn in the “vars/fqdn.yml” file, I abstract the target hostname, making my playbook more reusable and adaptable. This means I can easily shift the targeted host without altering the playbook’s underlying logic—just a simple update to the fqdn.yml file is needed.

In my AWX inventory, by naming my host “rancher.local,” I seamlessly integrate this FQDN setup. AWX, utilizing Ansible in the backend, resolves “rancher.local” to its corresponding IP address during runtime through my DNS setup. This approach ensures consistency with my playbook’s design and centralizes my infrastructure management, making it more manageable.

By confirming that everything is functioning as anticipated, I acknowledge that my setup is correctly utilizing FQDN for clearer, more manageable network communication and automation tasks. This strategy aligns with the best practices in system administration and infrastructure automation.

Part 1

GitLab and AWX installation and configuration

If you do not have GitLab and AWX installed I recommend to watch and read these tutorials:

Starting work with AWX, the open-source version of Ansible Tower, requires several steps to configure and launch your first job. Below is a detailed step-by-step guide to help you achieve your goal:

Step 1: Adding Inventory in AWX

The first step is to add a new inventory in AWX. This is where we will define our devices and hosts that we’ll be working with. In the AWX interface, find the ‘Inventories’ section and click ‘Add new inventory’. Name your inventory appropriately, for example, ‘Kubernetes Cluster’.

- Creating a new inventory:

- Navigate to the “Inventories” tab and click “Add”.

- Name your inventory and define it as needed.

- In the inventory, you can add groups and hosts that will be the target of your Ansible playbooks.

Step 2: Adding a Host to the Inventory

After creating the inventory, it’s time to add our hosts to it. In our case, we’ll add a host with our FQDN domain name. In the inventory panel, select ‘Hosts’ and click ‘Add host’. In the ‘Name’ field, enter your domain name, for example, ‘rancher.local’, instead of the traditional IP address. Remember, using FQDNs increases readability and simplifies management.

As you can see on my video, in AWX, in inventory called rancher, I defined a host, assiged to rancher inventory. In the field called name, instead of IP address I typed rancher.local for this host.

Step 3: Configuring the GitLab Repository

Next, we’ll configure our GitLab repository. We need to create a vars directory in the main directory of our project. In this directory, we’ll create a file named fqdn.yml. Open this file and add a line defining our FQDN, like so:

| |

Save and close the file. Remember to push the changes to the repository.

Step 4: Modifying the Ansible Playbook

Now that we have our variables ready, we need to update our Ansible Playbook to use this information. Open your playbook and ensure it defines using variables from the vars/fqdn.yml file at the beginning:

| |

This change allows Ansible to dynamically use the FQDN value that has been defined in our GitLab repository, increasing the flexibility and scalability of our operations.

Step 5: Creating a Job Template

- Creating a job template:

- Navigate to the “Templates” tab and click “Add” → “Job Template”.

- Name the template, select the project you created earlier, and the playbook you want to run.

- Select the inventory you will use.

- In the “Credentials” section, add the credentials necessary to connect to your servers (e.g., SSH keys).

- Save the template.

Step 6: Running the Job Template

- Launching the job:

- Find your Job Template on the list and click the “Launch” button next to it to start the job.

- You can follow the execution of the job in real-time.

Additional Tips

- Automation: Consider using AWX features to automate job launches, e.g., through schedules or webhooks.

- Documentation and Help: The official AWX documentation is an excellent source of knowledge about advanced features and troubleshooting.

To update systems using different package managers like apt, with Ansible, you can write a playbook that detects the operating system (or its family) and applies the appropriate update command. Below is an example playbook that accomplishes this task.

| |

Explanation:

- hosts: {{ fqdn }}: It is a variable placeholder in Ansible that should be replaced by the actual fully qualified domain name of the target hosts or an Ansible group name from your inventory

- become: yes: Elevates privileges to root (similar to sudo), which is required for package management. = vars_files: is a directive used to include variables from external files into your playbook. The vars/fqdn.yml is a path to a YAML file that contains variable definitions.

- tasks: The section of tasks, where each task updates systems with different package managers depending on the operating system family.

- when: A condition that checks the type of operating system of the host to execute the appropriate update command.

- ansible.builtin.<module>: The Ansible module responsible for managing packages on different operating systems.

- stat module: Used to check for the presence of the

/var/run/reboot-requiredfile in Debian-based systems, which is created when an update requires a restart. - reboot module: Triggers a system restart if needed. You can customize this module by adding parameters such as

msgfor the restart message,pre_reboot_delayfor a delay before restarting, etc. - register: Stores the result of the command or check in a variable that can later be used in conditions (

when).

Notes:

- update_cache: For package managers that require it (

apt), this option refreshes the local package cache before attempting to update. - upgrade: no: This ensures that the check does not actually update any packages.

- cache_valid_time: This prevents the task from updating the cache if it was updated recently (3600 seconds in this example).

- changed_when: This custom condition is used to determine if updates are actually available. For

apt, it checks the command output. - upgrade: For

apt, thedistoption means a full distribution upgrade.

Customization:

You can customize this playbook by adding additional tasks or modifying existing ones to meet the specific requirements of your environment, such as adding a system restart after updates or filtering updates for certain packages.

Important Notes:

- It’s recommended to test this playbook in a controlled environment before running it in production, especially the sections responsible for system restarts, to ensure all tasks perform as expected and do not cause unintended service interruptions.

These preliminary tasks ensure that the system updates and potential restarts are only performed when there are new package updates available, saving time and reducing unnecessary changes in your managed environments.

Focus on this task in Ansible playbook:

| |

Adding an option to reboot the machine after an update in an Ansible playbook can disrupt the AWX job, especially when you upgrade the host on which Kubernetes and AWX are installed, due to several reasons:

Service Interruption: AWX runs as a set of containers within a Kubernetes cluster. If you initiate a reboot of the host machine as part of an update process, it will lead to the temporary unavailability of the AWX service. During the reboot, all processes, including the Kubernetes pods running AWX, will be stopped. As a result, the AWX job that initiated the reboot will lose its execution context — it will not be able to monitor, manage, or report the status of the update process or the reboot itself because the AWX services will be down.

Job Incompletion: When the host reboots, the AWX job may be marked as failed or incomplete because the reboot process interrupts the job execution. Ansible (and consequently AWX) relies on persistent connections to the managed hosts to execute tasks. A reboot breaks this connection, preventing AWX from receiving a successful completion signal from the updated host.

Data Integrity and State Management: If the AWX database or other crucial services are not properly shut down before the host reboot, there’s a risk of data corruption or loss. Additionally, AWX needs to maintain state and context for running jobs; a sudden reboot could lead to inconsistencies or loss of state information.

Dependency on External Factors: The reboot might depend on various external factors, such as network configurations, boot settings, and services’ startup sequence. If these are not properly configured, the host might not return to its desired state automatically after the reboot, affecting not only the AWX instance but also other applications running on the host.

Timing and Coordination Issues: In a production environment, especially when dealing with Kubernetes clusters, timing and coordination of updates and reboots are crucial. If a reboot is not carefully planned and coordinated within the maintenance window, it can lead to service downtime extending beyond acceptable limits.

To mitigate these issues, it’s recommended to:

- Plan updates and reboots during maintenance windows when service downtime is acceptable.

- Ensure that AWX and other critical services are properly stopped and that the system is ready for a reboot.

- Consider using Ansible’s

asyncandpollparameters to wait for the host to come back online after a reboot and then continue with the necessary post-reboot checks and tasks. - Use health checks and readiness probes in Kubernetes to ensure services, including AWX, are fully operational before considering the update and reboot process complete.

- If possible, avoid managing the Kubernetes host directly through AWX for updates and reboots. Instead, use separate mechanisms or direct management strategies to handle critical updates and system reboots to avoid disrupting AWX operations.

Part 2

By following these steps, you should be able to set up your K3s cluster’s DNS resolution to meet your specific needs while maintaining proper function for both internal and external name resolution.

Configuring CoreDNS in Kubernetes

Domain Name System (DNS) is used by Kubernetes, an open-source platform for orchestrating containerized applications, to enable communication between its many components.

CoreDNS and ExternalDNS are two crucial technologies for DNS management in a Kubernetes cluster.

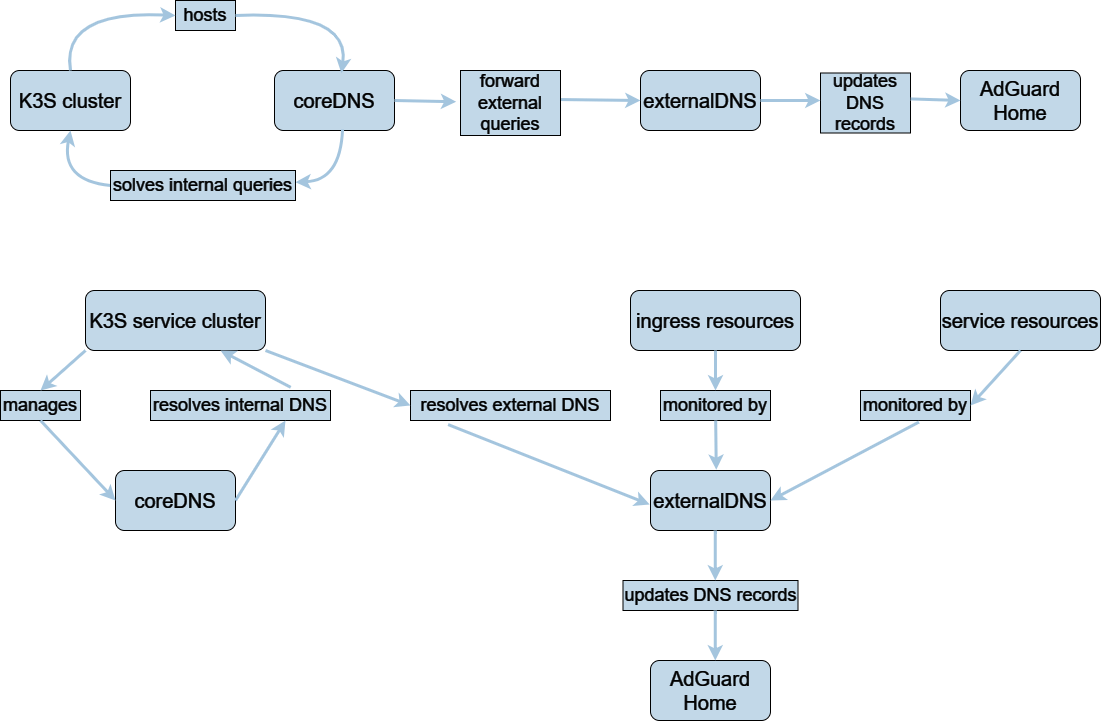

How CoreDNS and ExternalDNS Work

For its different components, including pods and services, to communicate with each other seamlessly, Kubernetes depends on the Domain Name System (DNS). The platform immediately creates a DNS record for a newly built Kubernetes service, making it simple for other pods to find and connect to the service. In addition, Kubernetes supports ExternalDNS, which makes it easier to set up and maintain DNS records for services that must be reachable from the outside world. As a result, accessing the services within the cluster is made simpler for external customers.

To put it another way, Kubernetes uses DNS to assist pods and services in locating and establishing hostname-based communication with one another.

- A DNS record for a Kubernetes service is automatically generated upon its creation.

- ExternalDNS, which assists in managing DNS records for services that must be reachable from outside the cluster, is supported by Kubernetes.

external DNS

To put it briefly, externalDNS is a pod that monitors all of your ingresses while it is operating in your EKS cluster. It automatically gathers the hostname and endpoint upon detecting an ingress with a particular host, creating a record for that resource in Route53. External DNS will instantly update Route53 if the host is modified or removed.

With the help of the supported DNS providers, this technology enables the automatic creation and maintenance of DNS entries for services that are publicly accessible. By resolving the service’s hostname to the external IP address of the Kubernetes cluster, it allows external clients to access the services that are operating inside the cluster.

coreDNS

Specifically designed for Kubernetes, this DNS server is currently the standard DNS server for Kubernetes 1.14 and higher. CoreDNS is an adaptable and expandable DNS server that may be used for name resolution and service discovery inside a cluster. With minor configuration adjustments, it can also be used to access external DNS providers.

The Reasons ExternalDNS Is a Useful Complement to K8s Cluster:

Kube-DNS, also referred to as CoreDNS, is the built-in DNS system for Kubernetes that handles DNS name resolution for pods and services inside a cluster. Nonetheless, because of a number of benefits, businesses frequently choose to use an external DNS system.

Advanced features: DNS-based traffic management, automatic failover, and global load balancing are just a few of the extra capabilities that external DNS systems can provide. Additionally, they have built-in security capabilities like DNSSEC, which guard against spoofing and tampering attacks. These characteristics are essential for businesses handling sensitive data, managing traffic across several locations, or managing heavy traffic loads.

Consistent DNS architecture: Whether or not a company uses Kubernetes, it may still maintain a consistent DNS infrastructure across all of its apps by utilizing an external DNS system. This improves security and streamlines management.

Dynamic and granular control over DNS records or text instructions kept on DNS servers is made possible by external DNS. Its main function is to serve as a bridge, making it possible to employ DNS providers with specific knowledge outside of Kubernetes. Millions of DNS records can be handled via external DNS, and it provides additional management possibilities.

Scalability: The Kube-DNS system may become a bottleneck when a Kubernetes cluster’s number of services and pods increases. In order to prevent the DNS system from becoming a bottleneck for the rest of the cluster, an external DNS system can manage a far higher volume of DNS queries.

Flexibility: You have more options when it comes to DNS server types when you use External DNS with Kubernetes. You can choose from a variety of commercial DNS solutions like Google Cloud DNS, Amazon Route 53, BIND, or Microsoft DNS, as well as open-source DNS options like CoreDNS, SkyDNS, or Knot DNS, Adguard Home, Pi-hole, depending on your needs and preferences.

An advanced and adaptable DNS infrastructure and management is available to enterprises by integrating an external DNS system with Kubernetes. Since Kubernetes may be used with a number of well-known external DNS providers, using an external DNS is advised when implementing Kubernetes in production.

CoreDNS is a powerful, flexible, and extendable DNS server widely used in Kubernetes. However, sometimes we need to customize its operation to our specific needs, for example, by redirecting DNS queries to external servers. How do we do this?

Let’s start by opening the CoreDNS configuration file, which you’ll find in Kubernetes named ConfigMap. I’ll show you how to edit this file by adding a ‘forward’ section. This section is responsible for redirecting traffic to an external DNS server.

It’s very important to make these changes carefully because errors in DNS configuration can cause connectivity issues throughout the cluster. After making and saving changes, we’ll restart CoreDNS so that the new configuration takes effect. Remember to check that everything works correctly after these changes.

You want to edit your CoreDNS configuration to add custom forwarding rules for external DNS queries. You can add these rules directly within the CoreDNS ConfigMap, specifically in the Corefile section.

Here’s what you should do:

- Save and the ConfigMap:

First, save the CoreDNS ConfigMap for editing:

| |

Then edit it:

| |

- Modify the Corefile:

In the editor, find the Corefile section. You will add custom forwarding rules under the existing forward . /etc/resolv.conf directive.

For example, if you want all DNS queries except those for internal Kubernetes services (cluster.local, etc.) to go to your home lab DNS server (let’s say it’s 10.10.0.108), while still maintaining Kubernetes internal DNS resolution, you can modify the Corefile like so:

| |

In this configuration:

- The

forward . /etc/resolv.conf { except ... }line is specifying that general queries should use the system’s resolv.conf (which typically points to the default Kubernetes DNS service), except for the specified internal domains. - The

forward . 10.10.0.108line then specifies that all other queries not caught by the first rule should be forwarded to your home lab DNS server.

- Save and Exit:

After adding your custom forwarding rules, save and exit the editor.

Kubernetes will update the ConfigMap when you will type the below command:

| |

It should display information

| |

- Restart CoreDNS Pods:

After updating the ConfigMap, you’ll need to restart the CoreDNS pods to apply the changes. You can do this by deleting the existing CoreDNS pods, and Kubernetes will automatically recreate them with the updated configuration:

| |

- Test the Configuration:

After the CoreDNS pods are up and running again, test the DNS resolution to ensure that:

- Internal Kubernetes services are resolved correctly.

- External domains are resolved via your home lab DNS server.

You can do this by exec’ing into a test pod within your cluster and using commands like nslookup or dig to resolve both internal and external DNS names.

| |

Revert changes

- Save and the ConfigMap:

First, save the CoreDNS ConfigMap for editing:

| |

Then edit it:

| |

- Modify the Corefile:

Revert back to this state:

| |

- Save and Exit:

After adding your custom forwarding rules, save and exit the editor.

Kubernetes will update the ConfigMap when you will type the below command:

| |

It should display information

| |

- Restart CoreDNS Pods:

After updating the ConfigMap, you’ll need to restart the CoreDNS pods to apply the changes. You can do this by deleting the existing CoreDNS pods, and Kubernetes will automatically recreate them with the updated configuration:

| |

Conclusion:

That’s all for today. I hope this tutorial was clear and helpful to you. If you have any questions or doubts, feel free to ask in the comments below. I also encourage you to subscribe to my channel and share this video if you find it valuable. Thank you for watching, and see you in the next tutorial!

Comments